A Guided Tour of the Abbey Church of St. Hildegard

The Abbey Church of St Hildegard was built between 1900 and 1908 under the auspices of Prince Karl zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg (1834-1921), one of the leading figures in German catholicism in the 19th century. Prince Löwenstein, who had made it his task to revive the monastic tradition of St Hildegard at the historic site, commissioned Fr Ludger Rincklage (1850-1927), a monk of the Abbey of Maria Laach and an architect by profession, to build the church. The foundation stone was laid on July 2nd, 1900; the church was consecrated on September 7th, 1908. Between 1907 and 1913 the interior of the church was painted, a project led by Fr Paulus Krebs (1849-1935) of Beuron, a student of the famous artist-monk Fr Desiderius Lenz (1832-1928), the founder of the Beuron School of Art. The abbey church at Eibingen is considered his most important work and one of the best complete compositions of the Beuron School of Art. The Abbey Church of St Hildegard was modelled on the old basilicas in the Romanesque style. The nuns‘ choir adjoins the presbytery of the church to the North, where the Benedictine nuns meet seven times a day for the Divine Office. The choir, as well as the South wall facing the choir, were altered in the 1960s. The wall paintings in this part of the church were whitewashed so that the murals in the interior of the church are no longer complete in their original form.

The visitor’s first impression upon approaching the abbey church will be that of the mighty twin towers, 45m in height. They are built of quarried stone, as is the church itself and all the monastic buildings, which was taken from the hill above the site. On the pediment between the two towers one can see the Crucifixion carved in red sandstone, showing Christ on the cross with Mary, his mother, and the beloved disciple John. Above the cross, as well as on the gable of the porch, and in the mosaic of the front wall of the entrance hall one can see the Cross of St Benedict, which immediately identifies the church as a Benedictine monastic church to the visitor. One also finds the same cross in the panels of the main entrance door to the church, which is made of bronze. The letters CSPB stand for „Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti“ – the Cross of our Holy Father Benedict.

The Beuron School of Art

On entering the church a unique atmosphere embraces visitors, inviting them to reflection. The spacious interior, designed in a symmetrical and serene form captivates, as does the muted, tranquil and seemingly mysterious colouring of the murals. Whoever perceives this unusually peaceful mood, has a fair understanding of the major characteristics of the „Beuron School of Art“.

The art of Beuron is a mystical, liturgical and therefore at the same time also a monastic-Benedictine art form, inviting the viewer to merely behold, adore and contemplate the nature and mystery of God. The art of Beuron breathes peace and, in a wonderful way, is timeless. In this respect, it has an affinity with its great model, the ancient Egyptian art. Architecture and painting, which are closely related, transmit an unwavering tranquility and majesty. The abstraction of all motion is executed consistently to the last detail: straight lines determine the appearance of the architecture; the strictly stylistic and stylized dominate the painting; the choice of colour is harmonious and uniform.

There is hardly a direction in art, which expresses resting in God, that essential feature of mystical contemplation, more clearly than Beuron. It may be difficult for many people nowadays, who appreciate art only for art’s sake, to grasp this „l’art pour Dieu“ (art for God). But someone, for whom art is content of thought – with more depth than the word – and who is willing to listen and to see, who lets himself be stimulated and be led into the mystery, to such a person these paintings will open up as a precious treasure-trove. He will be guided beyond himself and led into the infinite expanse of eternity.

Tabernaculum Dei cum hominibus – Basic Idea of the Murals in the Nave

The nave has four areas of wall paintings: both side walls, above the choir arch and the back wall. The space above the choir arch is dominated by the image of the City of God, by the walls of the heavenly Jerusalem, bordered by two towers each on both sides. The inscription in glowing ochre on sapphire-blue ground points to the basic idea of all the paintings and the theme of the murals in the church: „Tabernaculum Dei cum hominibus“, „the house of God amongst men“ (Rev 21:3).

The thought expressed here, God living amongst men, originates in the Old Testament. The place where the Israelites, the people of God, assembled – and therefore the very place of encountering God – was at the time of their wandering through the desert the „tent of meeting“, later the temple at Jerusalem. There, in „his city“ and „his house“, the Israelites celebrated and experienced God’s helpful presence. Symbolically, this Old Testament reference is also depicted on the back wall of the church over the great arched window above the portal. In the vision on Mount Sinai, God shows Moses the plan for his dwelling amongst men: „Inspice et fac secundum exemplar, quod tibi in monte monstratum est.“ (And see that you make them after the pattern for them which is shown you on the mountain.) (Ex 25:40). Moses saw the heavenly Jerusalem, which is depicted above the choir archway, on the plan. Ecclesiastical architecture in the Old and New Covenant is based on it.

In the same way, Jesus and the early Christian community regarded the temple as sacred and the „House of the Father“. But a new dimension was now added: Jesus himself through his death and resurrection became the final and universal place of encountering God and of God’s presence. Thus the Gospel speaks of his body as the true temple, and this is developed further in Pauline texts with the mystical body of the church, whose head is Christ. All the faithful therefore make up „the holy temple of the living God“. So the real place of his presence is the church as Christ’s original sacrament, as God’s people of the New Covenant. They gather to hear the Word of God, to pray and to come to the Lord’s Supper and thus turn the church building itself into the place of encountering God. This closes the circle. „Inhabitatio Dei cum hominibus“ (The in-dwelling of God with man) therefore becomes the symbol of the very history of God with man.

On either side of the choir arch we find St Benedict and his sister St Scholastica, the founders of the Order of St Benedict. St Benedict has his place at the northern (left) side of the arch and at the same time leads a procession of holy men in the upper area of the northern side wall. As a counter balance, the procession of holy women ends with St Scholastica. Both processions are decorated with palms, a symbol of life, which continues to be felt through these men and women into our present day. Beneath the founders of the order one can see on one side St Peter and on the other Moses with the Tables of the Law. Peter and Moses in turn complete a row each of figures on the side walls of the church: with Moses ends the row of the four great prophets – Daniel, Ezekiel, Isaiah and Jeremiah; with Peter ends the row of the four evangelists – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

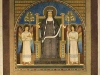

The Painting in the Apse

The interior of the church is characterized by the monumental figure of Christ above the altar in the apse. Painted on gold ground it reminds the viewer of a Byzantine mosaic – an association, which was definitely intended by the artist. Christ appears as Pantocrator, as sublime king and ruler of the universe, but at the same time man’s brother who receives him with open arms. The outstretched arms suggest the deep symbolism of this figure of Christ: The one who is invited comes out of his own free will and not by force. The relationship between Christ and man is a relationship of friendship and love. All are invited at any time and any place regardless of where they may be. In such a way, this figure of Christ is looking at each viewer; there is no place where he could withdraw to, to evade this gaze. This effect is due to the curve of the dome-shaped apse, which the artist at the Abbey of St Hildegard took full advantage of.

Below this image of Christ there is a frieze with thirteen lambs, a motif, which was already used in many churches in early Christian times. The thirteen lambs are a symbol for Christ and the twelve apostles. As a rule, this representation of Christ is considered a reference to the Eucharist, a celebration of Christ’s sacrifice. But here, the lambs cannot have this meaning as the picture is also a symbol for the apostles. Therefore a connection to Lk 10:3 suggests itself, where it says: „I send you out as lambs in the midst of wolves“. The apostles and consequently all Christians are not to bring the Good News and to build the Kingdom of Heaven with human power and strength, on the contrary: „…but God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong“ (1 Cor 1:27). The standards of divine love do not correspond to that which the world considers to be of rank and importance, but God works particularly in the inconspicuous and the weak: This is the message, which the thirteen lambs try to impress on the viewer.

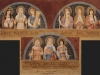

Below the frieze of lambs is a second frieze showing eight complete figures of angels, who are aligned in a strictly forward position and are clothed in white girded tunics (ancient Roman dress, on which the habit of the Benedictine order was based). Above their wings one can see the letters „SCTS“ – sanctus (holy), as a sign for the perpetual praise of God.

The Side Walls – The Story of Salvation in the Old and the New Testament

Scenes from the Old Testament are shown on the five panels above the arches on the southern (right) side wall. Viewed from back to front, the following motifs are shown:

1) Noah’s Ark, which was seen as a symbol for the church and was the preferred place of God’s promise.

2) God’s visit to Abraham and Sarah, when Abraham is told that he is to be the progenitor of God’s people.

3) Jacob’s dream of the ladder coming down from heaven, which is shown here as stairs between heaven and earth, with angels ascending and descending.

4) The procession of the priests with the Ark of the Covenant. This does not represent a certain procession but rather the Old Testament tradition to process with the Ark of the Covenant in general.

5) The altar, which is dedicated to „ignoto deo“, the unknown God. This picture expresses the idea of God also dwelling amongst the heathen and refers to the apostle Paul’s speech at the Areopagus in Athens (cf. Acts 17:22-31).

The middle frieze above the arches on the northern (left) side wall depicts five scenes, mainly from New Testament times, of God’s revelation to man. Again, from back to front these are:

1) Adam and Eve in Paradise. This picture is the first of the New Testament ones, as Christ’s redemptive work has Paradise as its starting point and wants to restore the inseparable union of God with man before the fall of man.

2) Christ’s incarnation in the manger at Bethlehem. In a unique way, the Word of God makes its dwelling with man through his Son.

3) The last supper with the disciples on Maundy Thursday and the institution of the Holy Eucharist.

4) The coming down of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost and the sending out of the disciples into the whole world.

5) The relationship between Christ and his church shown in the three symbolic images: bride and bridegroom, shepherd and flock and vine and branches.

Scenes Depicting the Life of St Hildegard

The paintings in the arches of the northern (left) side wall of the nave are dedicated to the Abbey’s patron, St Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179). As Fr Paulus Krebs considered himself the „painter of St Hildegard“, the paintings were executed with a special love and devotion. The five-part cycle of pictures shows important scenes from the life of the saint. Viewed from back to front these are:

1) St Hildegard goes to St Jutta to Disibodenberg. At the age of 14, Hildegard was sent to Jutta of Sponheim for education. From then on she lived with her in a cell, which was adjoining the monastery of Disibodenberg. During the course of the years the cell developed into a convent. At the age of 15 Hildegard took her vows. Later, after Jutta’s death, she was elected to be the spiritual mother of the community.

2) St Hildegard moves to Rupertsberg. In the year 1150 Hildegard of Bingen moved from Disibodenberg to Rupertsberg, where a larger house had been built on her instructions. Rupertsberg became her real monastic home – this is where she wrote her main visionary works. From here she founded the convent at Eibingen.

3) St Hildegard speaks to the Emperor Barbarossa at Ingelheim. Hildegard was not only an abbess and a prophetess, but also an advisor to many of her contemporaries. She corresponded extensively with well known and lesser known influential persons, and also went on several journeys in order to teach and to give advice. Up-river on the left bank of the Rhine at Ingelheim, the Emperor Barbarossa held court while his army was encamped there. He wished to meet the famous abbess. It is not known in detail what exactly the two discussed. But it is certain that the Emperor was obviously favourably inclined towards Hildegard and her monastery, and he issued a letter of safe-conduct for her in 1163.

4) St Hildegard founds the monastery at Eibingen and heals a blind boy in Rüdesheim. St Hildegard’s fame led more and more young women to the convent at Rupertsberg. But this house had originally been built for only 50 nuns.Soon it was too small and in the year 1165 Hildegard purchased the former Augustinian double monastery in Eibingen near Rüdesheim in order to re-settle the site. Hildegard remained abbess at Rupertsberg, but crossed the Rhine to Eibingen twice a week with a small boat. On one of these occasions she is said to have restored sight to a blind boy by moistening his eyes with Rhine water.

5) Signs appearing in the heavens on the death of St Hildegard. St Hildegard of Bingen died on the morning of September 17th, 1179. According to tradition, a wonderful light shone in the sky after her death, with a red shimmering cross being seen in the bright light.

The wall paintings in the side aisle are also dedicated to St Hildegard as well as other important women saints of the Benedictine order. Above the sacristy door on the eastern wall St Hildegard herself is shown with a quill in her right hand. Opposite, on the western wall, five holy women can be seen: Margareth of Rupertsberg, Hiltraud of Rupertsberg, Jutta of Sponheim, Ida of Rupertsberg and Elisabeth of Schönau. All five saints are stylized and have evenly proportioned faces. On the long wall between the windows more paintings of holy Benedictine women can be found.

They too, are not painted in a historically realistic way, but rather stylized, as a sign that the artist was not concerned with historical religious painting, but with symbolic character and its message of faith. On leaving the church one notices an inscription above the main door. This is dedicated in gratitude to the founder of the convent and builder of the church and monastery, Prince Karl zu Löwenstein. He laid the foundation to something still bearing rich fruit to this day. Every year many thousands of pilgrims and visitors come to the Abbey Church of St Hildegard. They come to Eibingen following the footsteps of the great saint and to praise God together with the nuns of the Abbey.

Exhibit of Beuronese Art and Murals of the Abbey’s Church

The occasion of the centennial celebration of the consecration of our church on September 7, 2008, inspired us to present an exhibition in the lateral nave which lasted six months and was dedicated to Beuronese Art, the history of the construction of our church as well as the murals found therein. As the exhibition received such positive resonance and was visited by an exceptional number of guests showing great interest in the subject, we have decided to make it available for viewing on our homepage. Sr. Teresa, Sr. Emmanuela, Sr. Philippa and Sr. Benedicta, with the inestimable support of Mr. Hans-Georg Kunz, began making preparations in 2007, as reported in our annual Chronicle.

The murals of our abbey church are regarded as one of the few remaining major and comprehensive works of the Beuronese School of Art. This style, which was almost forgotten, has recently experienced a modest renaissance and is receiving increased attention. It was developed in the last decades of the 19th Century and spread widely well into the mid-20th Century. The artists utilized forms and motifs from the classical Egyptian and Byzantine eras as well as elements of Art Nouveau which was developing at that time. The paintings have an almost timeless modernity due to their stylization. Unfortunately, significant portions of the church were painted over in the course of the 1960’s.

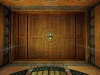

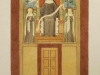

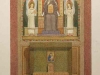

The exhibition shows how the church appeared originally.Displayed are mainly reproductions of original drafts which were previously unavailable to the public. They permit an exciting peek into the development of the paintings which can be seen in various drafts and in each phase of the process. New discoveries in the archives of the Archabbey of Beuron and in our own house permitted us, in addition, to create authentic, computer-generated photographic 3-D simulations. These computer simulations were constructed according to old plans of the nun’s choir and the presbyterium including the apse. The walls, floors and ceiling were reconstructed to scale measurements using submittals from the Beuronese School of Art. The virtual presentation was realized by utilizing original color sketches, contour drawings and old monochrome photographs which had been preserved in digital form.

We wish you great pleasure during your “walk” though the exhibition.

Your Sisters of the Abbey of Saint Hildegard